China Chic - How Chinese youth is reinventing culture, and reshaping luxury?

(research sample)

Client: SK-II

Market: China

Launch: 2022

While working on SK-II, I led a personal research project to better understand a market that defines modern luxury: China.

For decades, aspiration in China pointed outward.

But with Gen Z, something changed.

Western brands no longer carry the same mystique.

Instead, local culture is becoming aspirational again.

A shift that now shapes everything:

what people wear

what they celebrate

what lifestyles feel prestigious

what “luxury” even means

A shift deeper than consumption

What fascinated me most was that this wasn’t only aesthetic.

It was almost spiritual.

Gen Z consumers are rediscovering:

temples and meditation

traditional dress codes

local festivals like Qixi over Valentine’s Day

countryside lifestyles reframed as fashionable, not backward

The rise of Guochao (国潮)

Brands embraced this movement and Guachao was born. Literally “national trend”. This fulfilled a consumer appetite for brands that celebrate Chinese tradition with pride, not nostalgia.

In luxury, Guochao created two major consequences:

Western maisons localising

Sometimes beautifully done.

Sometimes criticised as appropriation.

The emergence of Chinese luxury players

Local brands claiming cultural identity as a strength.

Fashion

Western maisons localising

International maisons began moving toward real cultural collaboration, drawing directly from Chinese craft, history, and symbolism.

Fendi partnered with Yi artisans AXiWuZhiMo (embroidered textiles) and LeGuShaRi (14-generation silversmith family) to reinterpret the iconic Baguette through ethnic craftsmanship.

Loewe built an entire bag story around Chinese monochrome ceramics, inspired by historic glaze traditions and featuring contemporary ceramic artists.

Gucci introduced the Tian print, borrowing from 18th-century Chinese tapestries and bird-and-flower motifs to create a new accessories language.

Emergence of Neo-Chinese luxury brands:

ICICLE (之禾) staged its AW21 runway in Hanxi Village (Fuliang County), bringing fashion back to nature and countryside heritage, far from the usual global luxury codes.

Duanmu (端木良锦) revived the ancient craft of Chinese lacquerware through sculptural handbags.

Samuel Guì Yang represents a new wave of designers blending traditional Chinese dress references with contemporary tailoring. Less “retro costume,” more cultural continuity: Chinese codes made modern, wearable, and globally relevant.

Retail experience

Guochao reshaped luxury retail design, as brands began adopting local architectural and everyday cultural codes.

Louis Vuitton opened The Hall, its first restaurant in China, inside a heritage courtyard compound in Chengdu, drawing directly from traditional Chinese architectural language rather than a generic global luxury interior.

Prada transformed a Shanghai wet market into a branded pop-up, wrapping vegetables, stalls, and signage in Prada prints, elevating a deeply local everyday space into a luxury cultural moment.

Perfume

Fragrance has become one of the most dynamic categories in Chinese luxury, driven by local brands that treat scent as cultural storytelling.

DOCUMENTS (闻献) built a niche luxury world through striking art direction and historical depth, blending contemporary design with Chinese cultural references and ritual-like retail spaces.

Its positioning is often described as “Bold-Zen,” rooted in Chinese aesthetics and sensory heritage.Scent Library (气味图书馆) pioneered a nostalgia-driven approach to fragrance, creating scents designed around everyday Chinese memories.

Its cult bestseller “LBK Water” recreates the smell of liang bai kai (cooled boiled water), a sensory staple of childhood for many Chinese consumers.

Prestige slincare

Prestige beauty has become another frontier of Guochao, as Chinese brands increasingly treat wellness traditions and ancient techniques as sources of modern luxury.

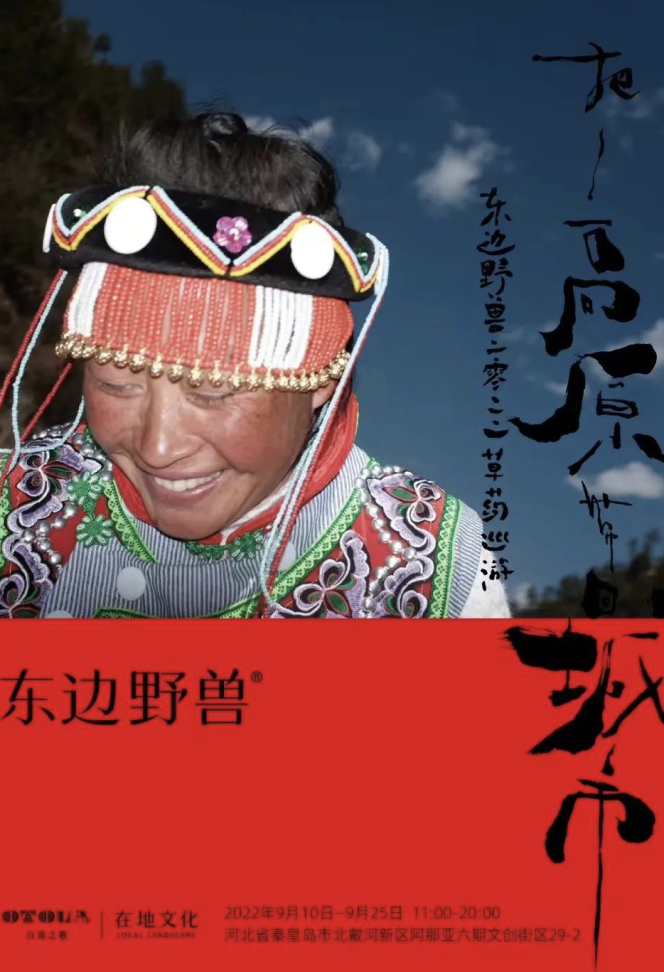

Herbeast (东边野兽) emerged as a premium “oriental herbal” skincare and lifestyle brand rooted in Chinese plant culture, Yunnan biodiversity, and contemporary art direction, reframing regional heritage as aspiration.

The emerging C-wellness label Fengsi (丰丝) has launched shampoo lines informed by ancient Chinese hair care practices, reviving traditional approaches and challenging prestige formulas long dominated by Western scientific authority.

Conclusion

Guochao shows that modern Chinese luxury can no longer be understood through Western prestige alone.

For brands entering China, credibility is not something you simply bring in.

It is something you earn by engaging seriously with local culture.

The brands succeeding are those that balance continuity and adaptation:

finding in “who you are” what resonates deeply within Chinese cultural pride.

This is what Loewe has understood through craft collaboration.

And what SK-II has long achieved with “mariage market” campaign.

The next chapter may be even more interesting.

As Chinese luxury brands grow stronger, and Western maisons become more culturally fluent, the influence may begin flowing outward.

China could become for luxury what South Korea became for culture.

Only on a scale that is, as always, disproportionate.

Exciting times ahead for Guochao.